Non profit

What road ahead for African immigrants?

Racial unrest in the southern town of Rosarno spells uncertainty for the future of Italy's African migrant workers

di Staff

The southern Italian town of Rosarno is calm after three days of racial unrest. This is the way the current situation is being depicted by numerous news agencies, but the problem is still far from being resolved.

Even though at least 1,000 African farm workers have been evacuated to immigrant detention centres in the cities of Crotone and Bari, a long term solution remains unclear surrounding the future of migrants – whether irregular or not –working in the fields across the whole of Italy.

“We have been talking about whether there is a problem of racism or not for four days now, but this is not the main point. We cannot find a solution this way. The problem in Italy is about laws. Italian laws about migration are absurd and are, made to produce these situations,” says Antonello Mangano, journalist, author of a book on African migrants and founder of terrelibere.org, a news platform on the region.

“What we need to do now is change these laws, in order to avoid provoking the same problems in other places at risk, for example Castel Volturno in the region of Campania or Cassibile in Sicily where the situation is not as extreme but still made up of exploitation. Giving legal documents to end the link between residence permit and jobs would be enough to obtain more dignified living conditions for workers. If we don’t understand this, we will see other riots in Italy and in the North too.”

The Pope has also spoken up about Rosarno. “We must get to the heart of the problem and go back to the meaning of the person. An immigrant is a human being, different in origin, culture, and traditions, but a person to be respected with rights and duties, particularly in the workplace, where the temptation to exploitation is easy, but also in scope of the concrete conditions of life. Violence should never be the way to resolve difficulties for anyone. The problem is primarily human. I ask you to look at the face of the other and discover that he has a soul, a history and a life and that God loves him as he loves me”.

He goes to the core of the problem, which had been underlined by Doctors Without Borders too, who have been working with migrants in Southern Italy since 2003. The project in the area of Gioia Tauro and Rosarno started on 15 December 2009, with the aim to give health assistance to African workers.

“The recent events of violence and hostility are an extreme symptom of the continuing state of abandon these workers employed in Southern Italy are subjected to,” says Loris De Filippi, head of projects for MSF Italy.

“They are a crucial work force in the agricultural sector in Italy, but at the same time they are vulnerable and easily fall victim to exploitation”.

“However, we have to say that the results of this assistance were not sufficient in taking them out from this condition,” says Tiziana Barillà, one of the founders of the Africalabria Observatory on migrant workers.

It is not just about health assistance however. African migrants have been brought far from the lands they were working on, far from the city that 20 years ago started receiving these people looking for a job.

“It is a real defeat for the part of Calabria which is against racism and bases itself on welcome. There is a lot of work to be done, not only where the ‘Ndrangheta* is strong”.

The subject of local mafia brings one to the heart of the region’s current situation, which Barillà describes as “explosive”.

“Two cultures have met, the mafia one, made up of violence and high-handedness, and the one that is spreading all over Italy, made up of fear for foreign people and xenophobia. Rosarno is a lesson to us about what happens when these cultures meet,” Barillà says.

But the role played by people involved in the local mafia is clear. Father Giuseppe De Masi, a priest, based in the area of Gioia Tauro, who works with the anti-mafia association Libera, has launched a strong j’accuse against the ‘Ndrangheta.

“Before African migrants took to the streets of Rosarno, the local mafia used to control their jobs and their salaries, but once they started the protest, they couldn’t just sit there and watch. They had to do something, because of the control on the territory that the mafia wants to keep”.

“Citizens of Rosarno have split into two parts: those who obeyed the ‘Ndrangheta’s will and those who were too scared to do something. With their act, African workers have taught inhabitants that people can rebel and walk on the streets holding their heads up high”.

By Chiara Caprio –

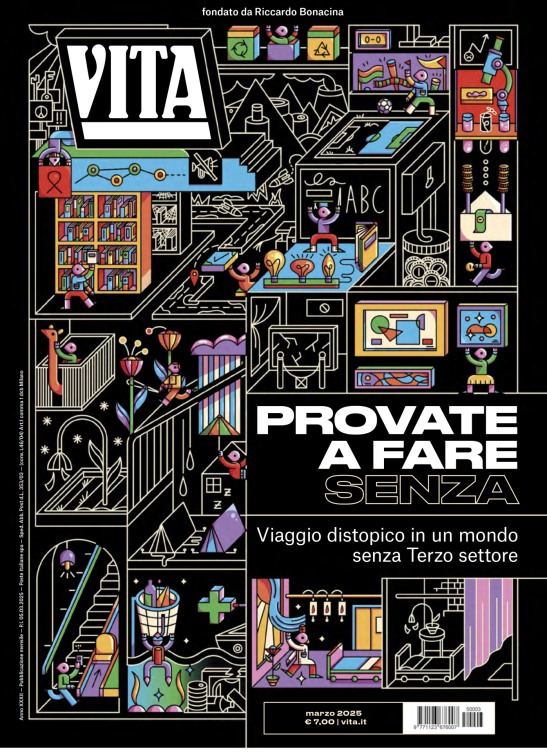

Cosa fa VITA?

Da 30 anni VITA è la testata di riferimento dell’innovazione sociale, dell’attivismo civico e del Terzo settore. Siamo un’impresa sociale senza scopo di lucro: raccontiamo storie, promuoviamo campagne, interpelliamo le imprese, la politica e le istituzioni per promuovere i valori dell’interesse generale e del bene comune. Se riusciamo a farlo è grazie a chi decide di sostenerci.