“Voluntary work is the soul of the third sector”, says third sector expert Jacob Beijer. Especially in Sweden, where 75% of the third sector’s work force are volunteers.

Jacob Beijer, 40 years old and native to Stockholm, is project manager for the neo-umbrella organisation Ideell Arena that aims to develop leadership qualities in the Swedish non profit sector. In the past he has worked for the Stockholm Region as board member, as Ombudsman for the High School Student Organisation of Sweden and as project manager for several non profit organisations including Next Stop Sovjet the MEGA Express, as well as having been the Secretary General for anti racism organisation Ungdom mot Rasism.

In much of Europe the devolution of public service provision to the third sector has brought governments to reconsider the role of civil society. Can the same be said for Sweden?

The short answer is: Yes. Two years ago Sweden elected a new, conservative/liberal coalition government. In their Declaration they declared that: “Civil society is the foundation of society, and the public welfare system is complementary to it”. This may be interpreted as a sign of revolution, since the former government, the Social Democrats, had never talked about civil society, let alone it being fundamental. But in actual fact there is still not complete consensus in Sweden that the welfare system should be financed through common means via the tax-system. The recent governmental declaration is more about changing the mind set, and starting to recognise the third sector and civil society as an important force within society.

The big change is, therefore, not about the funding of the welfare system, or about dumping health care on (cheaper) organisations that rely on volunteers, for example, but rather the creation of a real diversity of service providers. The government wants public, private and third sector producers to participate in all sectors of the welfare system, but for the system to continue to be funded publicly. In Sweden we have already seen this happen in pre-schools and schools, and now it is time for hospitals and other heath care institutions to follow suit.

To create this environment of diversity, and to strengthen the Third Sector, a general agreement, similar to the British compact, is about to be drafted between the public sector and the part of the third sector that operates in the social field, that is to say in the provision of welfare services. The question now is how this agreement will affect the independence and integrity of organisations.

What sets the Swedish third sector apart from other European third sectors?

The main characteristic of the Swedish sector is the high amount of voluntary work that is carried out. Almost 75% of all work in the third sector is carried out by volunteers. Compared to the average in other Western countries, which is around 33%, this is a huge difference. About 50% of the population in Sweden performs some kind of volunteer work, each one putting in, on average, 30 minutes free work every day (15hours a month).

This is the direct result of our tradition of forcing the public sector to take care of welfare production (even though this may well change soon, as mentioned above). The biggest part of the Swedish third sector is really about what individuals do in their spare time, after work and in weekends. This means activities like sports, cultural activities such as choir singing and other kinds of activities regarding housing, the Church, voluntary adult education Ö these are all major fields in the Swedish third sector.

The thing is that all these organisations traditionally also work with advocacy, so a voice for all these different interests is provided by a plethora of national umbrellas. Another characteristic is that in Sweden trade unions are considered to be part of the third sector, and they are still big and powerful.

You mentioned that 75% of third sector work is carried out by volunteers. What does this mean for young people who seek a career in the third sector?

Voluntary work is the soul of third sector organisations, and a prerequisite. They do not focus on fund raising so that they can pay salaries, but so that things can be achieved together. While it is true that there is a majority of volunteer workers, it is also true that there are increasing numbers of professional employed workers. However I do not think that youth generally see the third sector as a career opportunity, but rather as a place where they can gain important leadership experience. Many organisations are lead by young people.

Sweden is often considered a model in environmental matters. To what extent has the third sector contributed to this?

Again, a short answer: The third sector has, and does, play a major role here. I think that our tradition of voluntary work as a means of promoting social change can explain this. Simplifying things a little, the Swedish sector was founded with what we call “Popular Movement Organisations”, in the late 19th century. Three different popular movements were created at more or less the same time: the Labour Movement, that aimed to change the conditions for the new working class; the Nonconformist Church Movement, that aimed to promote the free practice of faith; and the Sobriety Movement, that wanted to do something about the widespread abuse of alcohol. They were all very successful and since then, when Swedes want to change things, their answer is to create an organisation. This was what happened in the 1970ís, with environmental issues, and the outcome was the creation of strong environmental organisations with hundreds of thousands of members.

What impact do social enterprises have in Sweden?

I am not an expert in this field, but social enterprises do not, compared to many other countries in the West, make a major contribution to society. Only 6% of the third sector’s overall turnover is produced by social enterprises. The reason is that traditionally their role was covered by the public sector; note that we don’t consider the large old cooperatives and mutuals as part of the third sector, as they are in France.

However, a lot of things are happening in the social enterprise field, especially when it comes to small scale cooperatives and Csr related issues of private companies.

What challenges does the Swedish third sector face today?

It must deal with the fact that the sector is moving from its traditional fields, that are those of acting and giving voice to that of producing services. Can we manage the change without loosing our soul? Can we do both? What will happen to our volunteers?

Are there any particularly symbolic Swedish social or environmental campaigns?

Two spring to mind from recent years. The first is the very successful campaign carried out by the equal-rights movement for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people (LGBT) that has made a huge difference, both in terms of public opinion – the same rights, opportunities and obligations should be applicable for LGBT people as they are for everyone else in society – and in the field of legislation.

The second is to do with climate change, exemplified in the shift in attitudes towards cars. “Performance” is not what people talk about now days when they consider buying a new car; rather, they think about how to make the least impact on the environment as possible. For example, unlike the rest of Europe there is no major media debate about the price of petrol, and you get a cash repayment of 1000 euros from the state if you buy an environmentally friendly car.

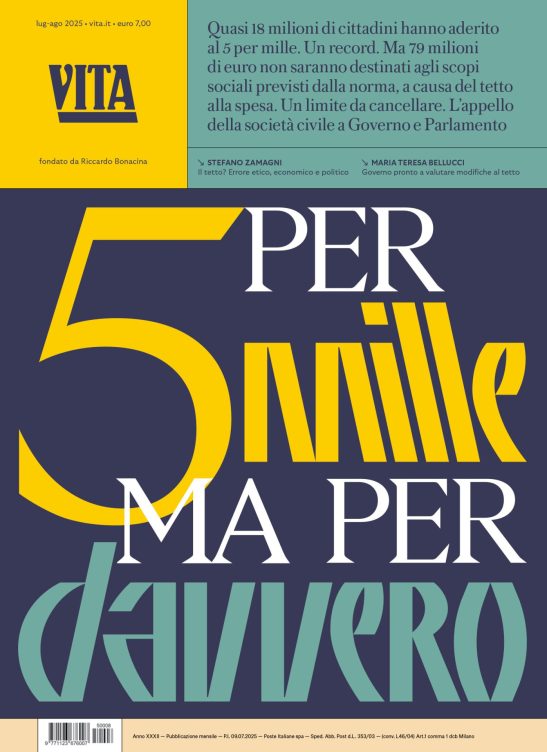

Vuoi accedere all'archivio di VITA?

Con un abbonamento annuale potrai sfogliare più di 50 numeri del nostro magazine, da gennaio 2020 ad oggi: ogni numero una storia sempre attuale. Oltre a tutti i contenuti extra come le newsletter tematiche, i podcast, le infografiche e gli approfondimenti.