“2015 is the tipping point for Norway. The fall of oil price combined with the recognition that climate change is going to affect the oil industry – the main source of revenue of the country – is forcing us to fundamentally reconsider our growth strategy”.

This was the opening line of Per Koch, senior advisor of Innovation Norway, as we joined him in the premises of the national agency for innovation.

Per captured the emerging consensus that we found in all the meetings we had in Oslo. The country is ready to move beyond its consolidated strategy based on oil and the welfare state, and develop a new culture of innovation and entrepreneurship building on its roots: collaborative leadership and commitment to social equality.

Innovation Norway has invited stakeholders from all over the country to contribute to the so-called ‘Dream Commitment’, an open debate on how Norwegian industry can overcome challenges such as climate change and the post fossil fuel economy. The choice of applying crowdsourcing to the national innovation policy made by Anita Krohn-Traaseth, the new CEO of Innovation Norway, epitomises Norwegian ease with openness and equality. We will see the results in May.

Norway is paving the way for the renewal of public good creation, a new economy for commonwealth. It’s a vision that recognises the welfare state and public goods as true sources of innovation and creative industries. It’s a challenge to the neoliberal paradigm which sees renewal as coming only from private enterprise.

In our view, the path Norway wants to take is an innovation strategy for the 21st century. It sees welfare services not as costs but as fundamental investment for open innovation and growth. Innovation should not be an opportunity for the few only. It should be democratised and distributed so as to tackle the causes of growing inequality. It has to put systems building at its core and challenge the silos culture that has compartmentalized sectors and raised walls between organisations.

Such an understanding of reality requires us to move beyond the atomistic interpretation of the world. It challenges us to reconcile state sovereignty, corporate independence and citizenship in a multi-systems society characterised by interdependence and reciprocal responsibility. It’s a reality in which regulation and the economics of offsets are not sufficient. This is the 21st century world where systems governance, finance, leadership and economics give birth to a new conception of the role of the state.

The fact that this conversation is taking place in Norway is grounded on the structural and cultural approaches to equality and responsibility for the social in the Nordic countries, underpinned by collaborative leadership and long term thinking.

If Innovation Norway is right, even the national statistics on economic prosperity and country ranking for innovation will have to change. Then Norway would become a reference and an inspiration for the rest of the world.

Here are some conclusions of the research project undertaken by the Young Foundation in September. Funded by Husbanken, the bank for social housing, and Oslo Municipality, the project was initially focused on a mapping exercise to draft the social innovation strategy for two neighbourhoods in Oslo: the Groruddalen and Tøyen. The project has been led in partnership with SoCentral, the local social innovation hub.

Supported by both YF’s and Husbanken’s staff, we interviewed almost 60 representatives of some of the main governmental, corporate and civil society institutions in the country. As well as Husbanken and Oslo Municipality, who are directly committed in the regeneration of the target location, we interviewed, the Norwegian Centre for Design and Architecture, DIFI – Agency for Public Management and eGovernment, Innovation Norway, Ministry of Health, Directorate for Work and Welfare, Association of NGOs, AMROP, Groruddalen Kommun, Askes Municipality, Norwegian Business School, Ferd Social Entrepreneurs, The Norwegian Fundraising Association, Norwegian Institute for Urban and Regional Research, Social Business Club, Framdrift Aktivitet AS, Corporate Spring and others.

A delegation from Husbanken visited the Young Foundation and other peer organisations based in London in January to increase knowledge-sharing.

What was planned to be a knowledge exchange and discreet intervention has turned into an opportunity to develop a new approach to address societal challenges through a participatory model and sustainable funding instruments. We call it the ‘Town Hall Model’ because this approach puts civic engagement at the centre of local development, building on systems financing and accelerators.

Here is an example. If you want to increase the educational attainment in a neighbourhood it’s not just a question of more funding for public schools or more private schools. You need to map and intervene in multiple factors affecting education in the area, such as investing in prenatal nutrition through breakfast clubs to increase children’ attention span, setting reading clubs to mentor pupils, mums’ associations to support young mothers, youth circles to provide peer support, and developing new tech to facilitate communication between parents and teachers.

Investment decisions need to be based on a system approach to identify the right intervention points. Decisions can’t be taken in a boardroom miles away from the neighbourhood, nor can they be justified by short-term results such as school-marks. Future benefits and savings from reduced crime, public health budget and unemployment costs have to be factored in. We call them ‘future public liabilities’ and reducing them justify this kind of investments.

The private sector has a role to play as well. Regeneration of a neighbourhood, for instance, is not just about new, shiny buildings. A prosperous neighbourhood is also made by its social capital, cultural diversity, local services and green areas. It is this kind of neighbourhood that turns out to be the most valuable investment in the long run.

We are in discussion with property developers to reinvent regeneration along these principles in the UK. In Norway, Husbanken is in the best position to host the same conversation.

Such interventions require a different kind of leadership, one that overcomes organisational boundaries. It’s leadership for the reality of systems and is built on collective intelligence.

In the next steps, the Young Foundation will partner with SoCentral to test the Town Hall Model in a location in Norway. It could be Oslo or a different location. The call is open.

Innovation Norway wants to host a workshop on systems transformation in March and feed the outcomes in the new strategy for Norway that will be launched in May.

The final report of the project funded by Husbanken and Oslo Municipality will be presented to the stakeholders in April.

We also see it as an opportunity to connect the project in Norway to the other ones we are running in London, Portugal, Turin, and Malaga. It’s an opportunity to build a learning network, to influence the current debate on the role of private sector in public good creation, and contribute to new thinking on the role of public policy in addressing societal challenges. This is our SmallWorldLab (aka EuropeLab) in action.

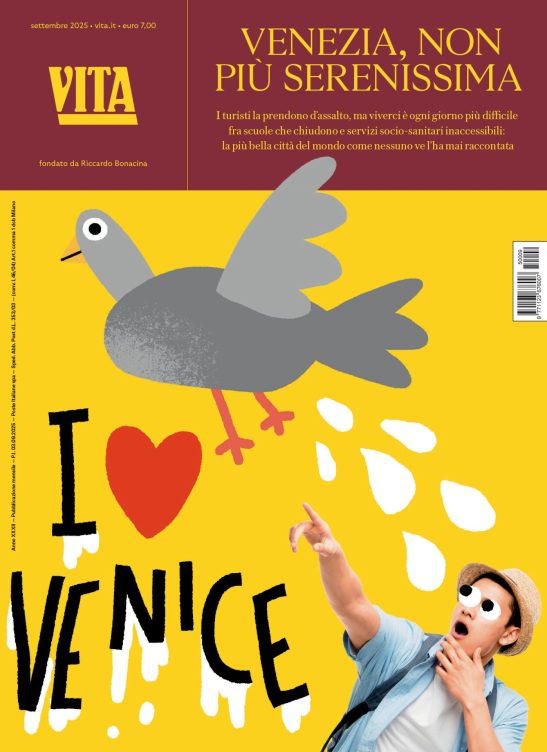

17 centesimi al giorno sono troppi?

Poco più di un euro a settimana, un caffè al bar o forse meno. 60 euro l’anno per tutti i contenuti di VITA, gli articoli online senza pubblicità, i magazine, le newsletter, i podcast, le infografiche e i libri digitali. Ma soprattutto per aiutarci a raccontare il sociale con sempre maggiore forza e incisività.