Non profit

Migrants, the usual scapegoats

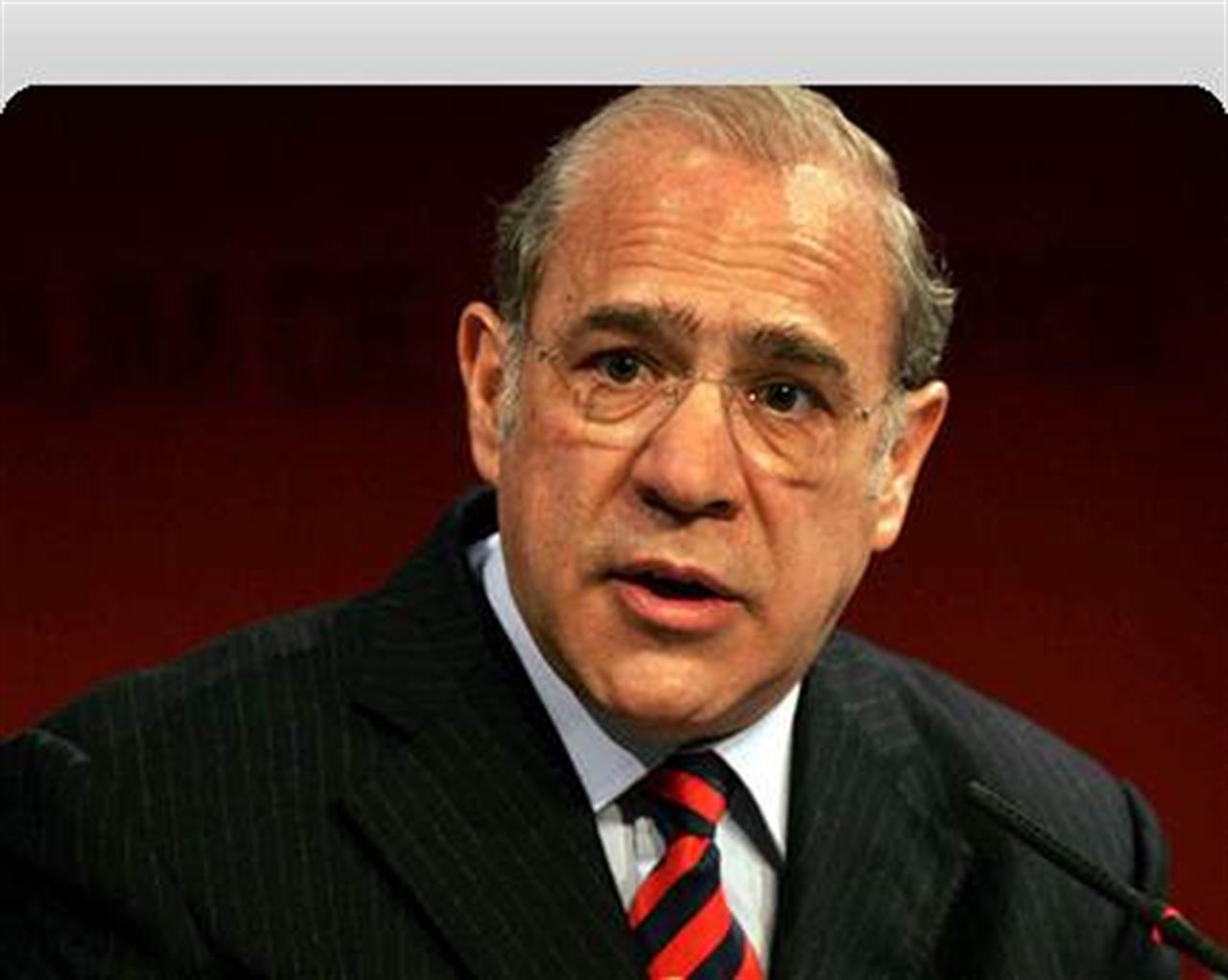

Interview with Angel Gurrìa, general secretary of the OECD

di Staff

By Joshua Massarenti, in Brussels

International migrants too are feeling the brunt of the crisis. So much emerges from a report published by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and presented in Brussels on July 12.

The 2010 edition of the “International Migration Outlook” reveals that in 2008, the last year for which there are statistics, “the inflow of immigrants to OECD countries fell by about 6% to 4.4 million people, reversing five years of average annual increases of 11%”. Moreover, “recent national data suggest migration numbers fell further in 2009”.

The OECD report highlights the difference in data between so called “permanent” and “temporary” migrants. The influx of ermanent migrants, which is to say those that have renewable working visas, has decreased by 7% while that of temporary migrants has decreased by 4%. Migrations caused by family reunions, on the other hand, have increased by 3% compared to 2007 as have the number of asylum seeking migrants (+14%). “But what concerns us more than these conflicting statistics is the fact that migrant communities are the first victims of the crisis”, says the general secretary of the OECD Angel Gurrìa, who in this exclusive interview with VITAeurope points his finger at the migratory policies of rich countries. And highlights a couple of paradoxes.

What should we learn from this report?

The economic crisis is obviously having an effect on migratory patterns, especially those that are tied to employment opportunities. At the same time, there is a whole category of migrants with valid working visas who have lost their jobs due to the crisis; unfortunately, as soon as there are economic difficulties, migrants are the first to get the sack as often they have the most precarious work contracts. With the exception of the UK, unemployment figures for migrant communities are higher than those of locals. Having said this, there is a paradox in the Old Continent: on the one hand there are higher unemployment rates than there have been since the Second World War, on the other there are companies in desperate need of staff. This contradiction is overshadowed by the preoccupation of European leaders with the worries of their citizens and who continue to present migrants as a threat rather than a resource.

What added value do migrants have in times of crisis?

Rich countries just have to come to terms with it. If you look at demographic patterns for the next 10 years, it is strikingly clear that the arrival of new migrants is crucial to counteract the aging European population. Take Spain, for example. At the end of the 90s the Spanish pensions system was risking a lot. Birth rates had dropped and life expectancy had peaked and the pensions of millions of Spanish people were at risk. Now, the economic boom Spain experienced between 1998 and 2008, especially in tourism, was fuelled by construction work and the influx of 5 million immigrants. Most of these were young, single, healthy migrants who had a very low social cost. The Spanish government saved its pension scheme for the next 15 years thanks to their taxes.

Which OECD countries have developed positive migratory policies?

There are three: Canada, Australia and the UK. These three countries have created long term migratory policies based on the continued presence of migrants within their boundaries. The governments of these countries are convinced that economic development depends on immigrants and their families. Of course, today the situation is more complex, especially in the UK. Like the rest of Europe, the English government now must give the priority to its second and third generation migrants. They are a potentially huge workforce but risk falling outside of the labor market if not protected.

Related Story:

Vita Europe talks to Dr. Emma Clarence of the OECD’s Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Center, in Trento, Italy. An expert on social exclusion and the role of the social economy, Clarence explains the role social enterprises play in creating more socially inclusive economies.

Click here to read more.

Si può usare la Carta docente per abbonarsi a VITA?

Certo che sì! Basta emettere un buono sulla piattaforma del ministero del valore dell’abbonamento che si intende acquistare (1 anno carta + digital a 80€ o 1 anno digital a 60€) e inviarci il codice del buono a abbonamenti@vita.it