Non profit

Is capitalism morphing philanthropy?

NYT looks closer at the “true motives” of some charities and the corporations that support them

Are American charities really exchanging political favours for corporate cash? At least a dozen of them are suspected of doing so, says the New York Times. “The Gray Lady” documents who is misusing philanthropic foundations to drill money out of big companies’ marketing office and who is so generously giving money to congressional charities in order to have certain laws changed or written. Such conclusions have surely upset more than one congressman in Washington, DC.

Big sponsors such as AT&T, Chevron, General Dynamics, Morgan Stanley, Eli Lilly and dozens of others — contribute millions of dollars annually in gifts to foundations. Donations range from token amounts to checks for $5 million. The non profits in question are in some cases owned, founded and managed by congressmen, like the Joe Baca Foundation (a charity Joseph N. Baca, member of the United States House of Representatives since 1999, set up three years ago to aid local organizations).

“Since 2009” Eric Lipton, staff writer at the New York Times, says “businesses have sent lobbyists and executives to the plush Boulders resort in Scottsdale, Ariz., for a fund-raiser for the scholarship fund of Representative Steve Buyer, Republican of Indiana; sponsored a skeet shooting competition in Florida to help the favourite food bank of Representative Allen Boyd, Democrat of Florida; and subsidized a spa and speedway outing in Las Vegas to aid the charity of Senator John Ensign, Republican of Nevada.” So what’s the problem? “Almost all of these foundations, they were set up for a good purpose,” says Mickey Edwards, an Oklahoma Republican who served 16 years in the House. “But as soon as you take a donation, it creates more than just an appearance problem for the member of Congress. It is a real conflict.”

Altria, the cigarette maker, for example, sent at least $45,000 in donations over a six-week period last fall to four charitable programmes founded by House members — including Representative John A. Boehner of Ohio, the Republican leader, and Mr. Clyburn, the Democratic whip — just as the company was seeking approval for legislation intended to curb illegal Internet sales of its cigarettes.

Moreover, like Mr. Baca, members of Congress benefit from the good will that their corporate-financed philanthropy generates among voters. Lawmakers confirm – according to Eric Lipton – the donations have no influence on the politicians’ work. Politicians also say that they typically do not serve on the charities’ governing boards or solicit contributions themselves.

There is no doubt though, that big corporations’ gifts to a politician’s favourite causes can generate expectations that the lawmakers might consider while on duty. The Office of Congressional Ethics, a House monitoring group, investigated last year lawmakers’ charities but took no action. Despite rules imposed in 2007 to restrain the influence of special interests in Congress, corporate donations to lawmakers’ charities have continued, thanks to a provision that allows businesses to make unlimited gifts to these organizations.

What about Europe?

From Lisbon to Vilnius the situation is certainly more complicated because these are different rules for the 25 different countries. “The article brings up, nevertheless, a non secondary issue, indeed what we have been calling “Philanthrocapitalism” as for example proposed by the duo Gates & Buffet,” Filippo Addarii, Euclid network Executive Director says. “There might be similar foundations across Europe, aiming to gain money or political consensus for their founders. What we need in those cases is more transparency and rules about international governance. But it all depends on the country you are in. In Italy a political foundation clearly states what the charity is to avoid this kind of dangerous misuses,” says Mr. Addarii. “The European Commission invests money and time to fight against terrorism but often lacks the resources to fight against crime, misuses and abuses generally and in the non profit sector. This is especially true in Eastern European countries».

On the other hand the situation is complicated and different in Europe, most of the European non profits prefer not to comment. The debate has just started and there is no doubt it’s going to continue.

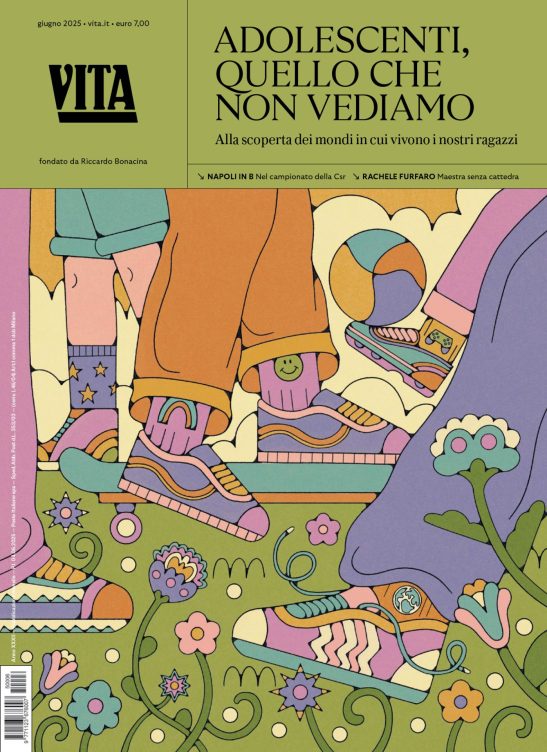

Si può usare la Carta docente per abbonarsi a VITA?

Certo che sì! Basta emettere un buono sulla piattaforma del ministero del valore dell’abbonamento che si intende acquistare (1 anno carta + digital a 80€ o 1 anno digital a 60€) e inviarci il codice del buono a abbonamenti@vita.it