Mondo

Freeganism: the sustainable movement against waste

Freegans in the UK claim that food waste is the big unspoken environmental crisis of our times

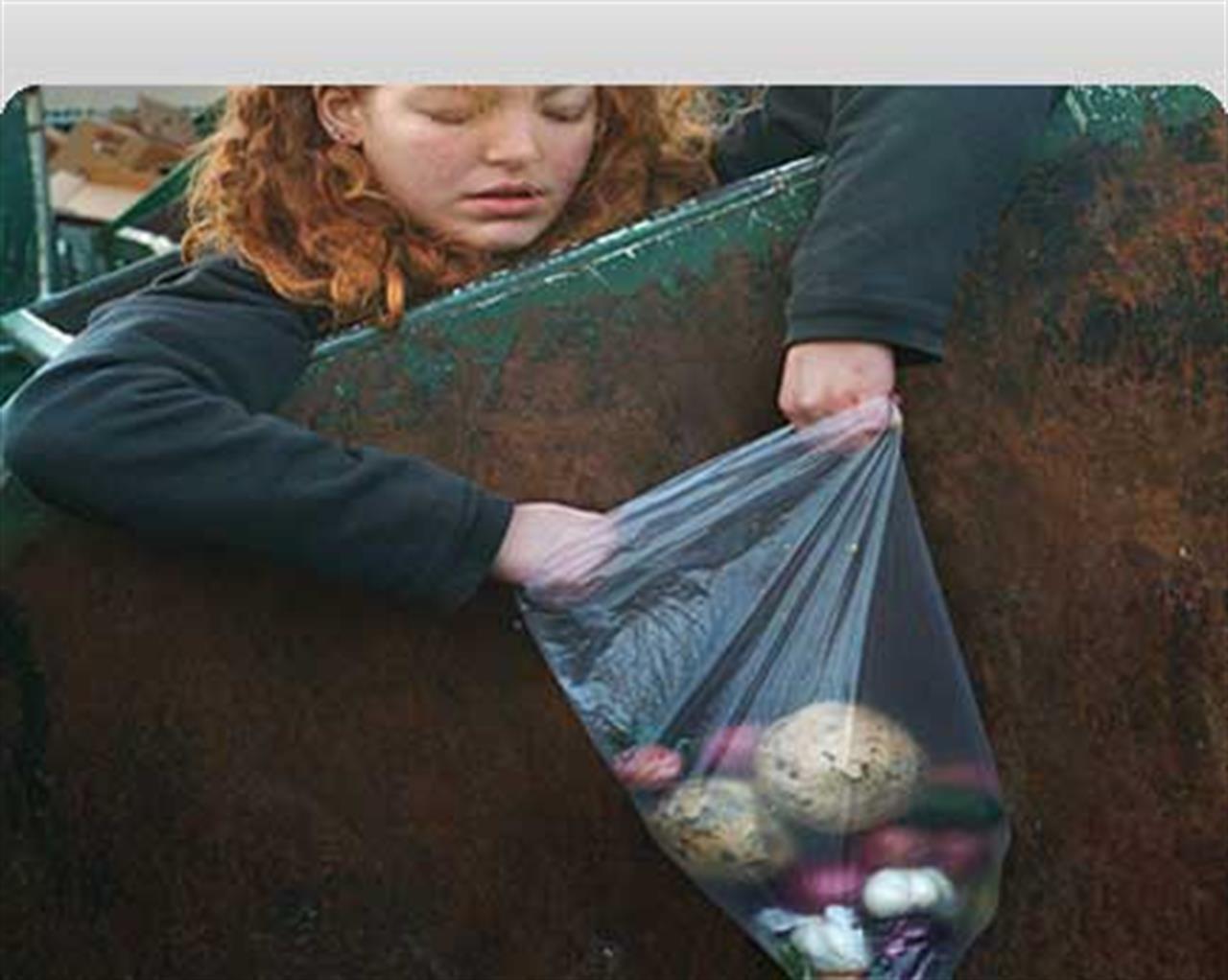

Britain, as a nation, throws away millions of tonnes of food each year – a quarter of all we buy. Enter the ‘freegans’ – campaigners like Tristram Stuart who are tackling the scandal of global waste by digging around in supermarket bins for their weekly shop.

Freeganism is a somewhat ill-defined activity that is best thought of as a subset of the larger anti-capitalist and environmental protest movements. Its origins go back to the Sixties and the embrace of alternative, anti-consumerist lifestyles, though Stuart claims that there is also a powerful inspiration for it in the Gandhian idea of non-violent action. In the US especially, freegans are often called “dumpster divers”, though many freegans insist that the practice of extracting food from dustbins represents only one strand of what they do; other freegan practices include co-operative living, squatting and “freecyling”, or matching things that people want to get rid of with things other people need.

Because freeganism is so ill-defined, it isn’t clear exactly how many freegans there are, and nor is there any one clear statement of their aims and motivations. The nearest thing to a manifesto is “Why Freegan”, a 1999 pamphlet written by Warren Oakes, drummer of US punk band Against Me! Even that, though, had trouble pinpointing what freeganism is.

What is clear is that people embrace freeganism for different reasons. For some, it is part of a general desire to opt out of the capitalist economy. For others, it is more about reducing their impact on the planet and living with a clear conscience. And for others still, no doubt, the motivation is to save money. Stuart’s reasons for being a freegan, on the other hand, are both very clear and highly specific. It is a way to protest against what he sees as the shocking extent to which our society wastes food. “If we didn’t needlessly throw so much food away,” he says, “I’d stop being a freegan.”

Most people would admit that wasting food is not good. But surely, they’d say, the problem can’t be that serious? Isn’t rooting around in rubbish bins a somewhat extreme – and unpleasant – reaction? Stuart would disagree. In his new book, Waste: Uncovering the Global Food Scandal, he sets out in forensic detail exactly why we should all be worried by the problem. In his view, food waste is the big unspoken environmental crisis of our times, right up there with more familiar concerns such as deforestation, water scarcity, even global warming.

Addressing food waste, he says, is a vital step when it comes to sorting out many of these other problems, and it’s hard to disagree with his logic. If we waste less food, we’ll need less land to grow it on, and hence will cut down fewer trees; we’ll use less water to irrigate that land and less carbon to transport and process the food it produces. On a more basic level, food waste is an issue of equality. If we didn’t waste so much food, there would be more available, which means fewer people in the world would go hungry.

Consumer waste represents just the tip of the iceberg. Although individuals contribute a massive amount to food waste, even more occurs further back along the supply chain. A huge amount is wasted during or immediately after harvesting, especially in developing countries, where poor transport and other infrastructure mean that food often perishes before it gets to market.

Then there are the unwieldy and complex workings of the global supply system: to get from its source to our plates, much of the food we eat undertakes a journey of epic proportions, involving carts, ships, planes and lorries, warehouses, processing plants and supermarket distribution centres. At each stage of this journey – inevitably, perhaps – a proportion gets wasted. When all this is added together, Stuart says, it is possible to estimate that more than a third of global food supplies is wasted (with the proportion in rich countries being as much as 50%). At the same time, nearly a billion people on the planet live close to starvation.

It is hard to say exactly how much food British supermarkets waste, because many of them are secretive about it. They are not required by law to reveal how much food they throw away (although some, such as the Co-op, do so voluntarily). According to data obtained by the Environment Agency, total UK retail food waste is 1.6 million tonnes per year. However, because of the limited nature of the information, and the fact that it was all self-reported rather than externally audited, the true figure may well be higher.

A further complication is that supermarkets are actually responsible for causing a lot of waste that occurs elsewhere in the food chain. “Think of their policy of insisting that all vegetables are of a uniform size and shape,” Stuart says. All supermarkets reject a portion of their supplier’s produce – some surveys suggest as much as 40%. “This forces farmers to throw a substantial proportion of that crop away, or at least divert it to animal feed, which is an inefficient use of resources.” Then there are the supermarkets’ notoriously capricious ordering practices, under which they reserve the right to change at the last minute, say, an order for a batch of sandwiches. “The suppliers are left with perfectly good food that they can’t get rid of and which they end up throwing away.”

Surplus stock could be redistributed. In the US, such schemes have long been popular. Giving away surplus food is a well-established practice among US supermarkets and many towns and cities have “food banks” where the homeless and those on low incomes can pick up this surplus for free. In Britain, retailers and producers have been much slower catching on to the idea, and until recently redistribution was only ever undertaken on an individual, piecemeal basis – shops and restaurants allowing the homeless to take away unsold items at the end of the day, for example.

This is starting to change. It is now the policy of some leading sandwich shops and convenience stores (the highest-profile being Pret a Manger) to donate a certain amount of their unsold stock to homeless charities. Even more significantly, strides are being made towards establishing redistribution schemes nationwide. Fareshare, a charity whose work Stuart champions, leads the way here. It persuades food suppliers and retailers to donate their surplus food, which it then transports to homeless shelters and day centres all over the country through its network of distribution centres (it currently has eight).

Read full Observer article.

Waste: Uncovering the Global Food Scandal by Tristram Stuart is published by Penguin, £9.99. Tristram Stuart’s website is www.liber-ate.org

Vuoi accedere all'archivio di VITA?

Con un abbonamento annuale potrai sfogliare più di 50 numeri del nostro magazine, da gennaio 2020 ad oggi: ogni numero una storia sempre attuale. Oltre a tutti i contenuti extra come le newsletter tematiche, i podcast, le infografiche e gli approfondimenti.