Non profit

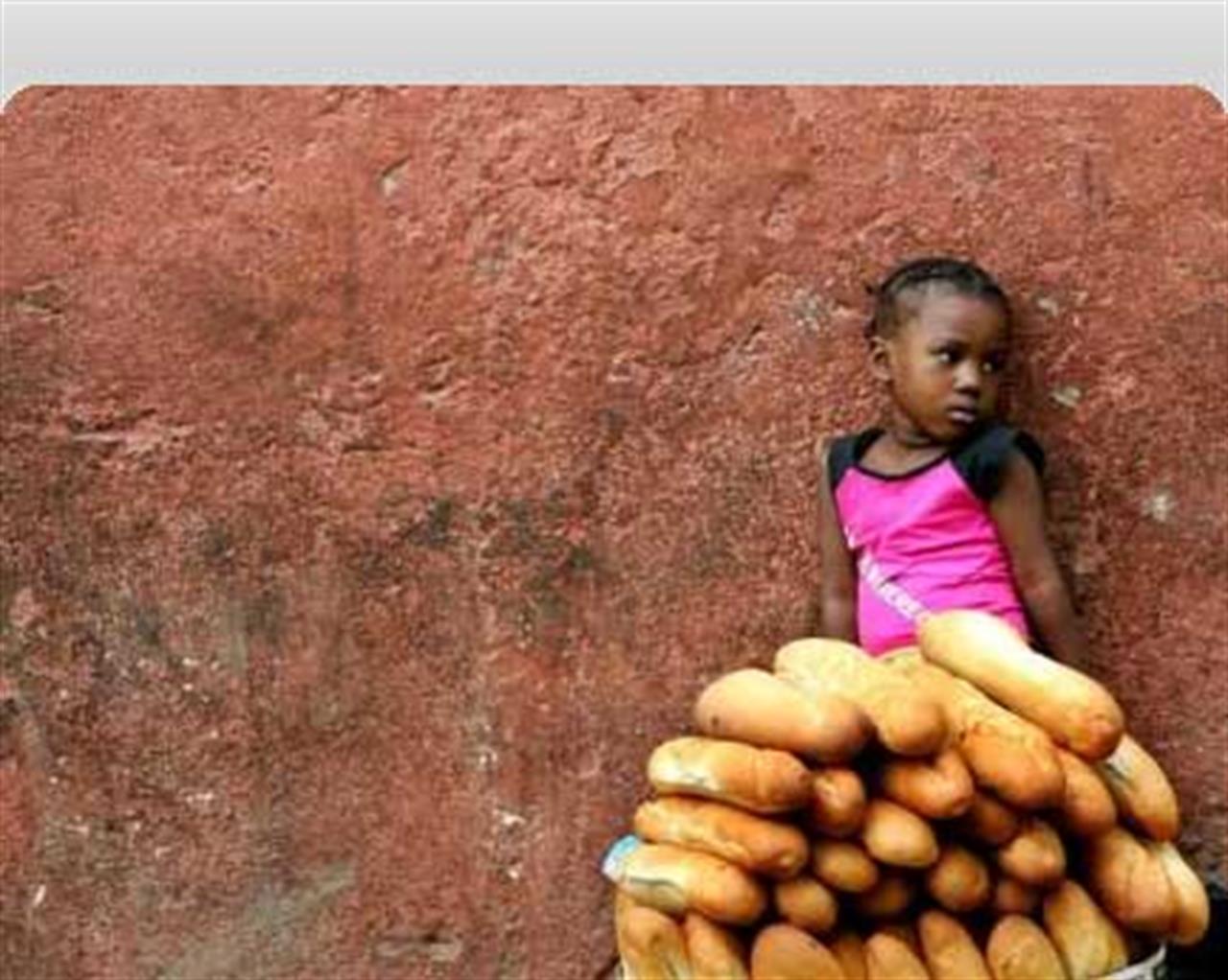

Development Aid in Africa: “a system fuelling inequality”

NGOs’ mistakes according to French anthropologist Giorgio Blundo: “Many projects are too often not coordinated. Development policies are used as power instruments. It’s time for the humanitarian world to examine its conscience.”

A few days before L’Aquila’s 2009 G8 Summit the issue of the day is neither hunger, nor poverty and not even the latest figures provided by the Fao on those hundreds of millions of people who in the world suffer from malnutrition.

In fact the issue of the day is a big tome of more than 500 pages written by Zambian economist Dambisa Moyo that tears to pieces international aid policies. Time magazine decided to put her in the list of the most influential people in the world for 2009.

A choice which has sent NGOs and activists committed to fight against poverty in Africa up the wall and which has made former United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan happy and persuaded that his book, Dead Aid: Why Aid is Not Working and How There is a Better Way For Africa “induces us to have a new approach towards Africa”.

According to Dambisa Moyo, aid has ended up creating a dangerous dependence and has jeopardized good governance, which is one of the “sine qua non” conditions to come out of poverty.

But is this really true?

Giorgio Blundo, anthropologist at French École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (High Studies School in Social Sciences), has an experience of years of research in Western Africa on crucial issues such as decentralization, local authorities and administrative corruption.

Professor Blundo, Dambisa Moyo is so angry with international aid that she has asked for the suspension in their activity until 2050. How do you react to this kind of provocation?

I must admit that I have thought about the problem many times with my colleagues. The kind of dynamics that aid produced over the course of the years doesn’t create a sustainable social-economic development in Africa. Nevertheless, to block aid completely means obliging some States to interrupt salaries’ payment to officials or prevent entire parts of the population from obtaining all kinds of public services.

The truth is that as years go by, “projects” have become a banal, daily element in the existence of rural and urban populations.

In the last four decades, there has been such an abundance of programmes, which were all too often not co-ordinated, and many local actors ended up appropriating the speeches, practices and trends of development imported from abroad to adapt them to their social, political, cultural and economic context.

What are the consequences of all of this from a socio-economic point of view?

Aid produced an array of material and symbolic resources which generated big forms of inequality. Too often, one speaks about the way in which States have redirected aid. However, maybe it’s right to highlight that many people, including those belonging to NGOs, have exploited development policies to create power spaces for themselves.

What role has civil society played?

During the last decade the new password of international organizations is “participation”, which means a strengthening of the role of civil society in development and promotion activities of “good governance”. Now, for the World Bank or IMF, civil society is represented by NGOs. Many of them do a very good job, still it is also true that, at least in Western Africa, many people, volunteering as middle-men between donors and beneficiaries , have exploited the possibilities offered by the world of cooperation to create a system of gains and of rents to reinvest in the local political scene. In fact, if in the past working in an NGO was humiliating, today professionalisation of African NGOs has made this job attractive. This system ends up fuelling inequality.

In an interview released a few weeks ago to Afronline, Ugandan journalist Andrew Mwenda affirmed aid won’t save Africa, but governments’ responsibility and the creation of a taxation regime will…

It is true. Working on the field I could notice, together with some other colleagues, a great expectation from many African citizens of different walks of life towards the State and its ability to provide quality public services. Now, to have these services the creation of a good system of taxation is necessary. Which means a propensity of citizens to pay taxes, but especially a propensity of governments to manage them well and to redistribute wealth. He who pays taxes has many expectations…

How could aid to development become more transparent?

The international community has been limiting its approach on technical issues for too long; as for instance to lower the costs of public administration, train officials or promote reforms of administrative decentralization. Unfortunately these interventions tend to hide the political dimension of the socio-economic dynamics caused by aid.

Every project creates struggles for power at a local level causing disequilibrium and readjustments. I think it is necessary to re-politicise reflection on interventions and on the role of middle-men in development. Another front is fight against impunity. It is a necessary condition if one wants to give credibility to interventions and to fight corruption that undermines relationships between citizens and States more efficiently, but also between African States and international community.

Media campaigns for public integrity undertaken by governments to keep on obtaining cooperation funds are not sufficient. A strong political will is necessary, supported by a public opinion that, though it is still in the making, is asking for the new foundation of African States increasingly loudly.

Cosa fa VITA?

Da 30 anni VITA è la testata di riferimento dell’innovazione sociale, dell’attivismo civico e del Terzo settore. Siamo un’impresa sociale senza scopo di lucro: raccontiamo storie, promuoviamo campagne, interpelliamo le imprese, la politica e le istituzioni per promuovere i valori dell’interesse generale e del bene comune. Se riusciamo a farlo è grazie a chi decide di sostenerci.