Non profit

Bridges in Venice are all up hill

Of 420 bridges in Venice only 20 are accessible to wheelchairs.

di Staff

According to official figures, only 2% of Venice’s historic centre is accessible to differently abled people. There are few of these areas, which are often isolated and mainly located near train and bus stations. Furthermore, Italian architect Santiago Calatrava has designed a famous bridge that links Piazzale Roma to Venice’s train station which is not accessible for people with disabilities.

It would seem that this city has too much art to be able to be accessible as well. History can’t be meddled with …

But reality tells us different: people with disabilities are able to reach 70% of Venice thanks to public transportation. Steamboats and motor-boats are equipped to carry one wheelchair at the least, even if not all of the dockings are built according to the rules. Informahandicap (a service promoted by the Venice municipality to give information on services, rights and facilities for people with disabilities) has drawn eight itineraries without barriers, that even include the islands of Murano and Burano. These itineraries are not just trips on a boat, they include guided tours to palaces, walks in little squares and, where possible, even crossing some bridges.

The accessible ramp

Bridges that are accessible to the differently abled are not many in Venice. About twenty out of 420. But they do exist. In most cases restoration works on bridges have modified the original steps, making them lower and wider, like the Guglie bridge, in the Cannaregio area. Although this solution only allows wheelchairs that are pushed by someone else to cross and that things are a little more complicated for motorized wheelchairs, it is still an option that means that the structural characteristics of the bridge remain intact. And it means the bridge is more accessible. The problem of adapting bridges is finding a balance between accessibility and artistic preservation; this role is taken on by the authorities and it is they who, on many occasions, have stopped projects to make the city more accessible to all.

Stair lifts, platforms that move on a track along the banister, are already widespread – one was even going to be added to Calatrava’s famous bridge. But invariably one of the authority’s architects or a municipality office brands them ugly, so they are removed. But if the truth be known, the stair lift’s main fault is not aesthetic. Rather, it is the fact that they need a key that is only available in a few offices, each with their own opening hours.

Venetians have tried other ways to beat the inaccessibility of canals. Footways to cross canals during restoration work on bridges are a temporary solution. Pity that they block boat traffic. Another two ways are the “caregòn” and elevator. The first, a horizontal platform parallel to the water, is useful, but is very invasive. The second, an elevator that goes from the ground to the span, has been tried on Longo bridge, on the Island of the Giudecca, but it’s too voluminous to be used everywhere.

Dreaming the Biennale

Ramps are another way to make bridges more accessible and they have been added only in those cases where there were big enough spaces to give an adequate slope. But even then there are those who complain, like the case of Sant’Antonio’s bridge. As a matter of fact citizens don’t criticize the decision to make the bridge accessible, but the fact that, instead of adapting the bridge during restoration works, a long inclined plane made of iron and wood, that doesn’t adapt well to the bridge stones, has been added later.

Now, all there is to do is wait for a special occasion, like the Biennale or the Venice Marathon. Then, temporary ramps made of wood or plastic, are placed around the city. This year, the marathon ramps will remain from October until the end of the carnival, allowing many people with disabilities to go to city areas that would otherwise be off limits to them.

Finding excuses for bridges built a long time ago is one thing, but it is harder forgive a contemporary project like Caltrava’s: 11 years of study and 13 billion euros mean that some solution was possible, but Calatrava didn’t manage it.

Translation by: Cristina Barbetta

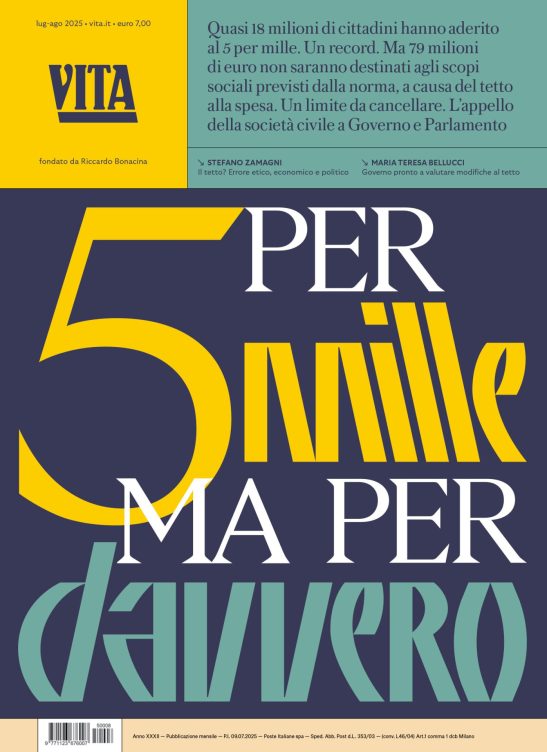

Nessuno ti regala niente, noi sì

Hai letto questo articolo liberamente, senza essere bloccato dopo le prime righe. Ti è piaciuto? L’hai trovato interessante e utile? Gli articoli online di VITA sono in larga parte accessibili gratuitamente. Ci teniamo sia così per sempre, perché l’informazione è un diritto di tutti. E possiamo farlo grazie al supporto di chi si abbona.