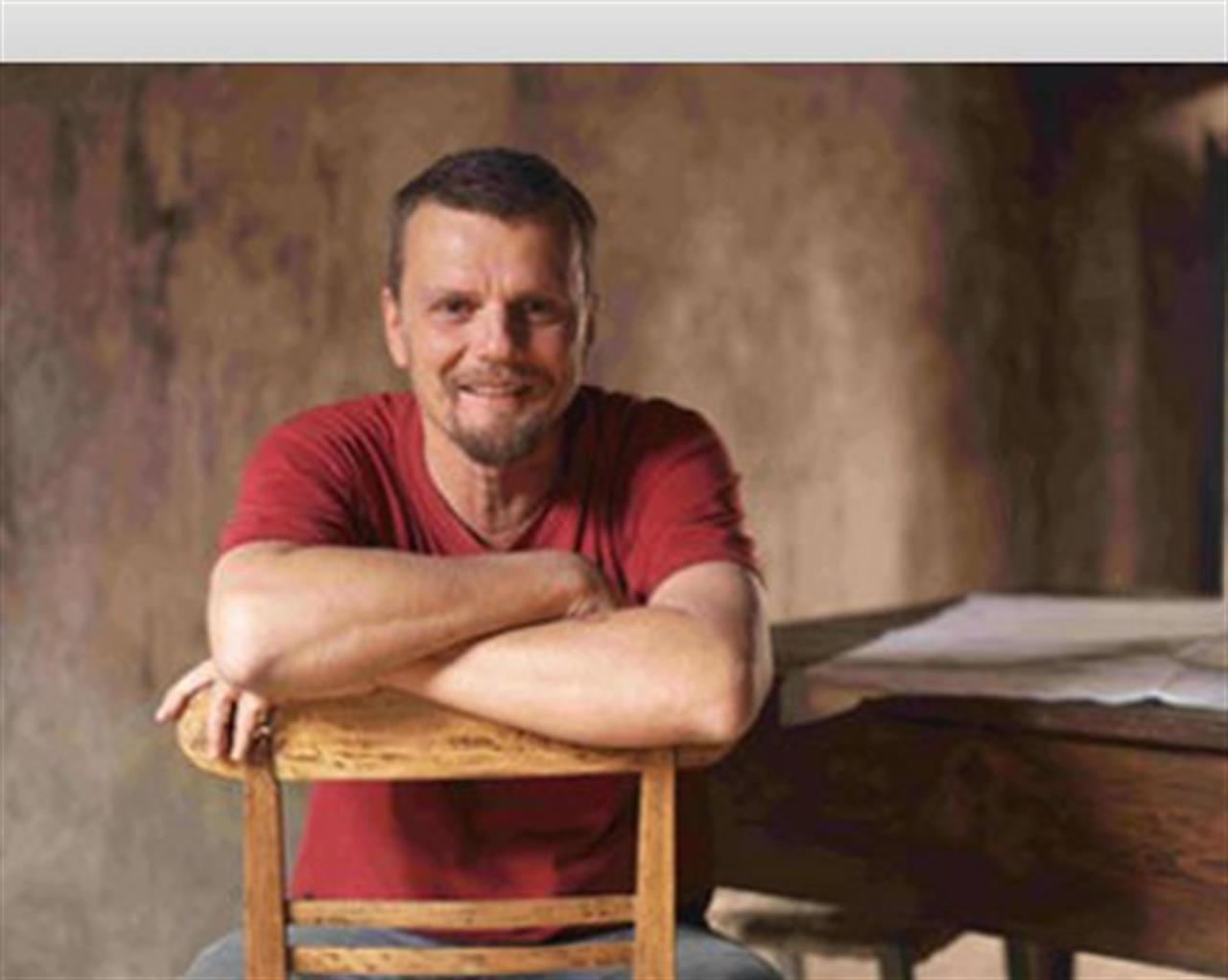

By Mattia Schieppati

Many mayors in Southern Italy, across Abruzzo, Basilicata and Calabria call it the “Kihlgren Method”.

In other words, for many local administrations it is the last occasion to bring back to life their small deserted villages.

Small villages in the mountains, and old towns that have been left from their inhabitants and are now silent. “I have about 300 e-mails from Italian mayors waiting to be read in my mailbox. According to them I should buy half of Italy, but this is not the goal of my project.” Says Daniel Elow Kihlgren, 45 years old, Italian on his mother’s side and Swedish on his father’s.

Since 1999, when he applied for the first time the method that is named after him he has been given various nicknames by the Italian and international press: “the Swedish who saves villages, the young patron”. According to the “legend” in 1998 while he was travelling across the Abruzzi Appennines he came across a vision that enthralled him: the semi-deserted village of Santo Stefano of Sessanio, 1250 meters on the mountainside of the Gransasso National Park, just half an hour from Pescara, but half a century from civilization. He thought about it a few seconds and then decided to contact the owners of the houses in the village, who had abandoned it, leaving it deserted, in order to buy them. In six years he bought and restored 4 thousand square meters of houses and he started a rigorous restoration project. He only used salvaged materials and original furniture and building techniques, creating a rambling hotel, with rooms distributed in the different buildings, putting some of these buildings for sale in order to recover the costs.

This intervention has brought the village back to life. “When I arrived in Santo Stefano there were only three accommodation facilities open during the summer. Now there are 15. Around 75 percent of the houses were deserted , and only a few elderly ladies; now Santo Stefano counts 120 inhabitants. Since 2008 the town has received 7300 tourists a year, while in 2001 they were only 280.

The method has been repeated in Matera, in 18 rocks which have been entrusted to the company by the city administration, without their history being taken away from them. And now he has seven more restorations to complete including small fractions, houses, historic centers around Abruzzo, Basilicata, Campania and Calabria.

Why has no one thought of this before?

Because unfortunately in Italy there has never been a landscape culture. If something doesn’t have a signature it isn’t considered an heritage. In Italy Giotto has to be protected as does Villa Medici, while these villages made of houses and walls built by unknown people are not the result of an aesthetic study, but the socio-anthropological product of a community. And that is why nobody is interested in them. They are not seen as cultural heritage. I might be crazy but I can’t find anything more seductive than these places, with their integrity. It is the heart of history that you feel coming out from these landscapes.

What is the “Kihlgren method” founded on? What is the difference between this activity and “normal” property speculation?

It is the respect, the love for the idea of identity that we have managed to impose. Before intervening on Santo Stefano we recorded hours and hours of interviews with people who once lived here but had migrated, in order to understand what the village was like back then. We only used salvaged materials. For the interiors we did some research with experts and now the houses are furnished with home handicrafts that were produced in Santo Stefano until the end of pastoral civilization. For the first time ever we have created a touristic destination without the usual cement disaster.

These places are still pure because the world has forgotten them. How are they going to remain intact now that even the New York Times is speaking about them?

I have thought about it ten billion times. The answer is in the agreement that we present the local administrations. We only ask for one thing: a commitment to preventing the construction of new houses. Only renovation, no new buildings.

Have you ever thought about exporting this model to some other villages in Northern Italy?

Yes, I have been asked to do the same things in other villages in the North. But in the Alps it is different, there is a great respect for marginal places: no one is ashamed of poverty. You will find young graduates living in the city, going to spend a day in the chalet where their grandfathers live. graduate young guy who lives in the city, spending a day in the chalet where his grandfather still lives. I hope that, also with a little help from us, the South of Italy will get over this “shame” and understand that they should be proud of their past, treat it as heritage.

The Identikit

Daniel Elow Kihlgren, half Swedish on his father’s side, was born 45 years ago into a well-off family of constructors. Raised in Milan, he travelled the globe and lived a restless youth . He studied philosophy and contracted the HIV virus at the age of 18. The virus lies dormant but causes him a constant fatigue. In 1999 he founded Sextantio, a society that purchases, restores and manages abandoned villages, converting them into hotels and buildings for sale.

Nessuno ti regala niente, noi sì

Hai letto questo articolo liberamente, senza essere bloccato dopo le prime righe. Ti è piaciuto? L’hai trovato interessante e utile? Gli articoli online di VITA sono in larga parte accessibili gratuitamente. Ci teniamo sia così per sempre, perché l’informazione è un diritto di tutti. E possiamo farlo grazie al supporto di chi si abbona.