Non profit

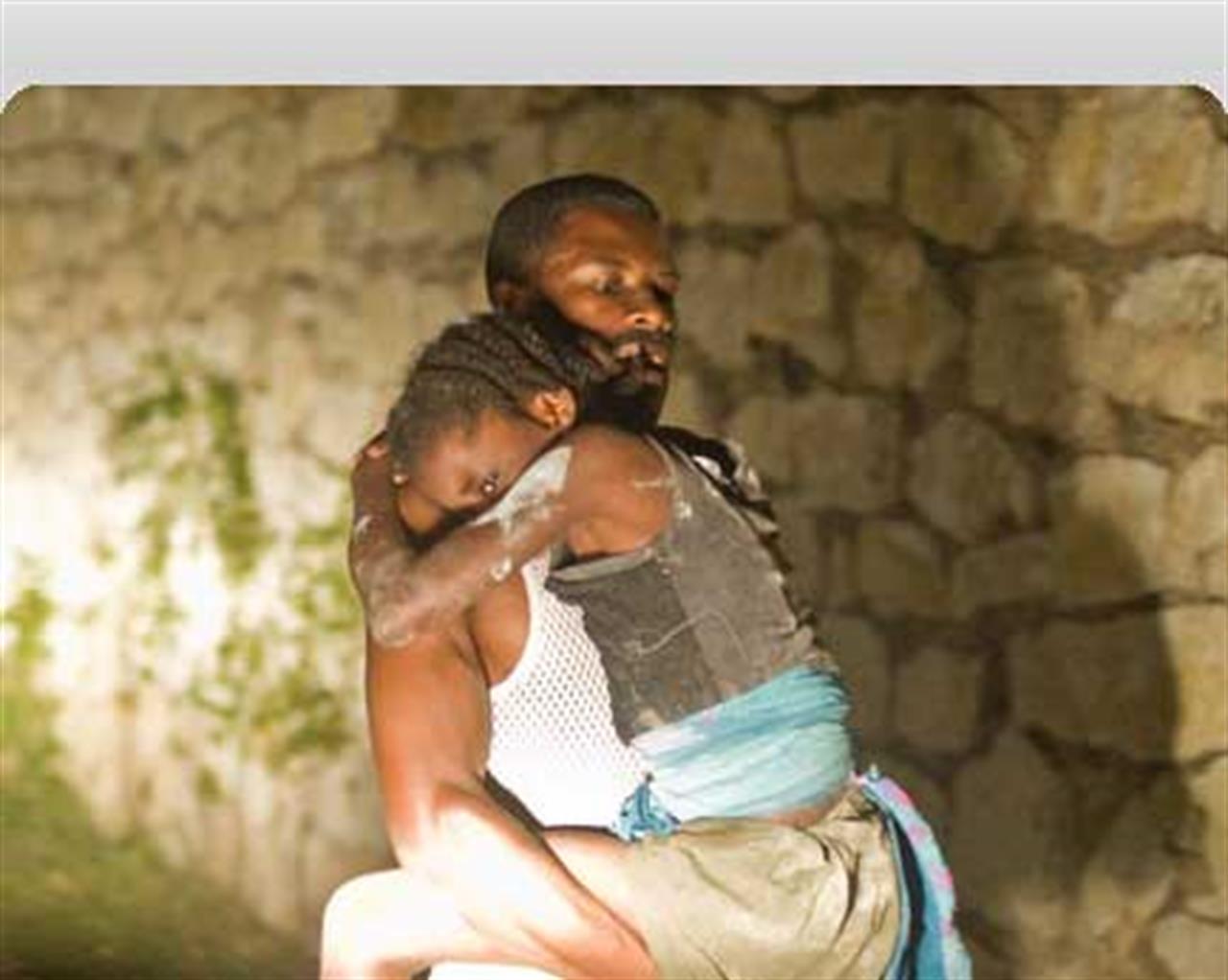

An extraordinary country brought to its knees

Interview with Haitian journalist Hegel Goutier

di Staff

“This cataclysm has brought us to our knees again.”

Haitian journalist, Hegel Goutier, talks to Joshua Massarenti of Vita about his homeland, the stories that haven’t been told and gives his own reflective point of view, taking the spotlight off the international relief workers and back onto the Haitians themselves.

Friday January 12 2010 at 4.53pm: the earth trembles. What do you remember of those moments?

As soon as I learned of the catastrophe, I wondered how I could make myself useful. Now, apart from the sheer impossibility to intervene physically in Haiti, the only thing that’s left to me is the power to communicate. That’s my job. Many Haitians living in Belgium were not managing to get into contact with their relatives and friends. I wasn’t able to get into contact with any of my relatives there either. […] One tries to pick up from the ruins in any way possible.

Haiti has been pushed into the spotlight by the international media. From these images and comments, has emerged a country which is cursed. How do you feel of that image?

In an interview with Le Monde a few days ago, one of my close Haitian friends Dany Laferrière talked about this curse saying it was “an insulting word, that insinuates that Haiti has done something bad and that it is paying for it.”

What happened in Port-au-Prince is an exceptional seismological happening which has absolutely nothing to do with the story of its people. But one extraordinary thing that this event has revealed to the world is the dignity of this people and the way in which they are facing the difficulties in which they have found themselves.

Despite this, we are hearing stories of gangs on every street corner, of the risks volunteers are running to save people…

I can’t deny the violence. It was there before the earthquake, it hasn’t disappeared. Continuing to speak of a country perpetually pursued by chaos is useless. If you follow that kind of logic, it’s not even worth sending money.

A few months ago I met the representative of the UN in Haiti – a victim of the quake – he was on his way through Brussels to meet members of the European Commission. At that time he told me that he had never witnessed a country make so much progress in such little time. Few people remember this today though, in the same way that few people will remember the extraordinary work of the former Prime Minister, Michèle Duvivier Pierre-Louis during her brief mandate (July 2008-October 2009). It was no coincidence she was chosen by the EU to receive the most important Journalism award in Europe.

But this can’t have disappeared from one day to the next…

Haiti is a country that is always at the cutting edge. Sometimes this is positive, sometimes this is negative. It is rarely in the middle. Its story is extraordinary, like its victory against the French in 1804. There are other less well-known events too, like what happened in 1946 and our ante litteram May 68. Estimé Dumassais was elected president giving way to a particularly fertile and innovative period. The greatest European intellectuals came to our country. I’m talking about Jean-Paul Sartre, Malraux and Anais Nin. We were one of the first countries in the world to authorise a communist party as well as an ethnology faculty.

This period I am referring to, which I would call the age of enlightenment came shortly after the American occupation (1915-1934), which is no surprise. Haiti was hungry for progress and freedom. In 1949, there was an incredible international exhibition in Port-au-Prince. This period lasted just four years, after which Dumassais became ill and a military government came into power.

What follows is the Duvalier era, one of the darkest periods of Haitian history…

Between François Duvalier and his son Jean-Claude, we went through very hard years. A dictatorship which all but eliminated the good work which had been done in the post-war period. Cité Soleil for instance was home to one of the most prestigious cultural centres on the island 40 years ago – now it is a slum.

When Jean-Bertrand Aristide arrived in 1990, we went through a sort of re-birth. After the coup in 1991 he could have come back even stronger, but the contrary proved true. Follows another long passage à vide until the election of René Préval in 2006, which is when things started to change again. Port-au-Prince seemed to regain its charm, gangs seemed to calm down. This cataclysm has brought us to our knees again.

What future for Haiti then?

That’s a difficult question to answer. For now, we are in the hands of the international community. At first I didn’t dare to believe that the richest powers in the world would be prepared to mobilise themselves to stop the worst and save lives. But now I see the mobilisation has been sincere. People need to act fast though and well. Simply putting back the current anti-seismic infrastructures will not be enough. A control organ needs to be installed with real powers to punish dishonest constructers.

And from an economic point of view?

We need to re-launch the rice fields. From being a exporter in the business, the country has become an importer in recent years. These days, American rice costs 10 times less than the local one. Urban violence that broke out two years ago during the food crisis was largely due to dumping policies exerted during the 90s by food companies.

With the earthquake comes the threat to social peace. But I believe in the nation of Haiti. You just need to think of the heroic intervention of the Léogane citizens to save the local textile factory.

The media has tended to focus on the extraordinary interventions of volunteers and emergency relief workers of Americans, French, Brazilians or Italians; but the first interventions came from Haitians who had no tools to go about their relief work. Without their courage, the number of victims would have been much higher.

By Joshua Massarenti

17 centesimi al giorno sono troppi?

Poco più di un euro a settimana, un caffè al bar o forse meno. 60 euro l’anno per tutti i contenuti di VITA, gli articoli online senza pubblicità, i magazine, le newsletter, i podcast, le infografiche e i libri digitali. Ma soprattutto per aiutarci a raccontare il sociale con sempre maggiore forza e incisività.