Politica

Damaging report for an ethnic profiling Europe

Ethnic Profiling practices have been found to be on the increase since 9/11 attacks, with worst cases found in Italy where ethnic profiling has been said to be intertwined with policy making

di Staff

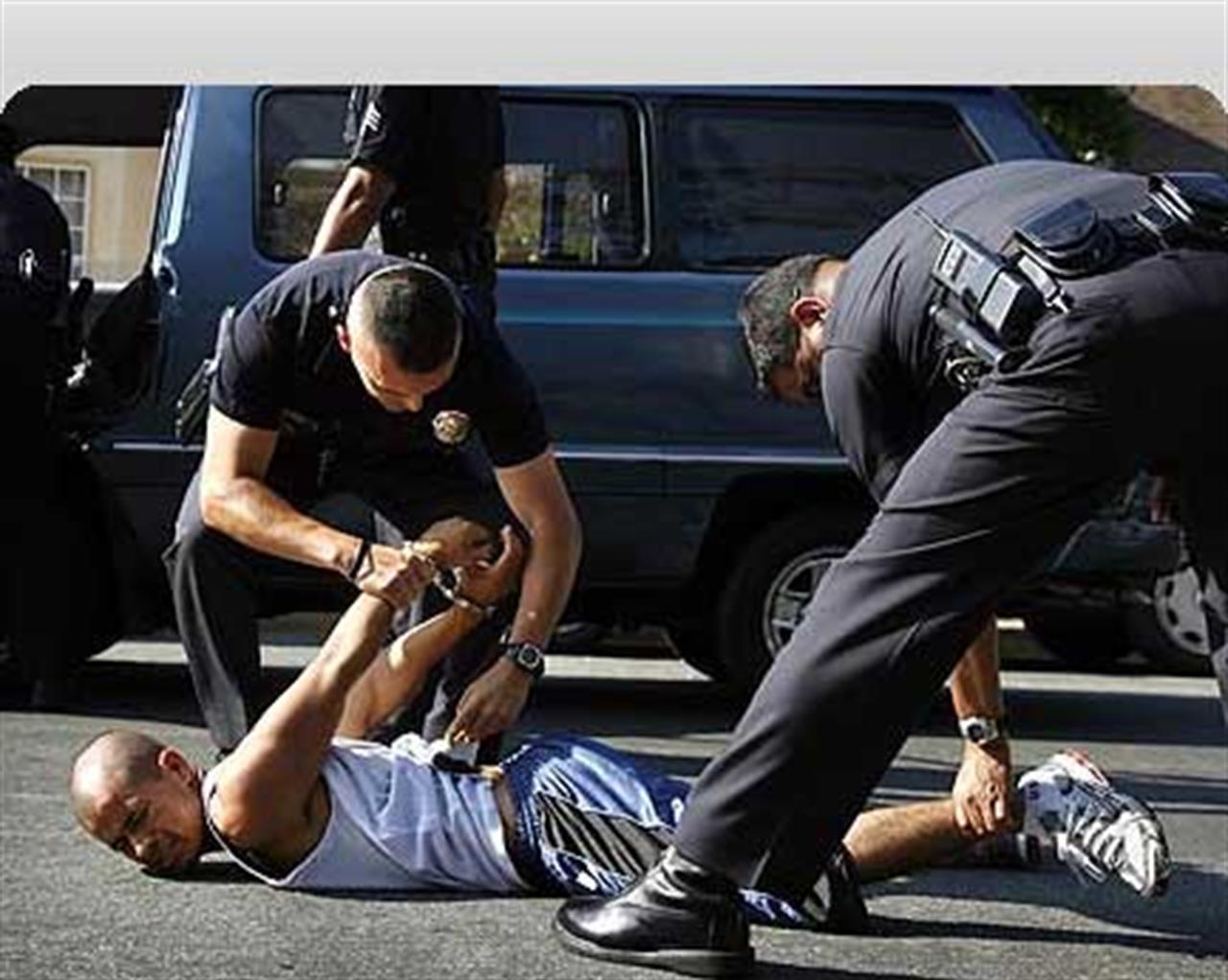

Ethnic and religious profiling is still widespread in Europe, although it is both damaging and ineffective, a report released on May 26 argues.

“Ethnic profiling” – a term describing the use of ethnic and religious criteria in law enforcement and investigative decisions about who may have committed a crime – has “intensified in recent years in Europe,” according to a study by the Open Society Justice Initiative, a programme of the Open Society foundation.

The practice has increased particularly since the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks in the US, it says. Stops and searches of British Asians have increased three times since then and five times since the July 2005 London bomb attacks.

A similar phenomenon has been observed in other countries, with German police conducting mass identity checks outside major mosques, and French and Italian police raiding homes, businesses and mosques targeting Muslims, “particularly those considered religiously observant.”

But in addition to clearly discriminating people on the basis of their religion and ethnicity, the method is highly ineffective in stopping crime, the study argues.

“There is no evidence that ethnic profiling stops crime or prevents terrorism. Separate studies in the United Kingdom, the United States, Sweden and the Netherlands have all concluded that ethnic profiling is ineffective,” it says.

‘Not all terrorists are Muslim’

Ethnic profiling “makes things worse,” argued James A. Goldston, executive director of the Open Society Justice Initiative.

“It humiliates people, it stigmatises whole ethnic communities and …that’s not only bad for these communities, but also for the police and everybody’s security, because it means that those communities don’t trust the police anymore and they’re not going to provide information on which police crucially depend in combating crime and terrorism,” he said at a press conference in Brussels.

“Not all terrorists are Muslim …There simply is not one terrorist profile. There’s not one set of characteristics that can help people focus on who will be a terrorist,” Mr Goldston said.

The study looked in detail at France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and the UK and while none of the countries stood out as a good performer, it found “at least a platform to move ahead” in the UK.

The country “systematically collects the [ethnic] data so it allows people to know the reality in a more complete way than is possible in any other European country at the moment.”

It also has “an explicit legislative prohibition …that applies its wide anti-discrimination norm to action by the police,” Mr Goldston explained.

Ethnic profiling and policy making

But in other countries, such as Italy, ethnic profiling has been intertwined with policy making.

“In Italy and in other countries as well, it’s very clear that immigration control policies …drive a great deal of ethnic profiling,” said Rachel Neild, Senior Advisor to the Open Society Justice Initiative.

“One of the things we were extremely concerned about in Italy was the way in which political leaders would conflate immigrants with terrorists …There was a great deal of language at one stage about all immigrants [being] potential terrorists, all Muslim [being] terrorists, etc,etc – which I think is deeply worrying,” she added.

The Open Society report recommends EU-wide legislation to clearly define ethnic profiling, ban it and even introduce sanctions against it.

“European law on matters pertaining to ethnic profiling is [currently] a complex patchwork of protection and gaps,” according to the report.

Additionally, the EU and national governments should fund projects to help police work better with the minorities in question.

Source: EUobserver

Report: www.justiceinitiative.org

Vuoi accedere all'archivio di VITA?

Con un abbonamento annuale potrai sfogliare più di 50 numeri del nostro magazine, da gennaio 2020 ad oggi: ogni numero una storia sempre attuale. Oltre a tutti i contenuti extra come le newsletter tematiche, i podcast, le infografiche e gli approfondimenti.