Non profit

Macedonia: effects of the global financial crisis

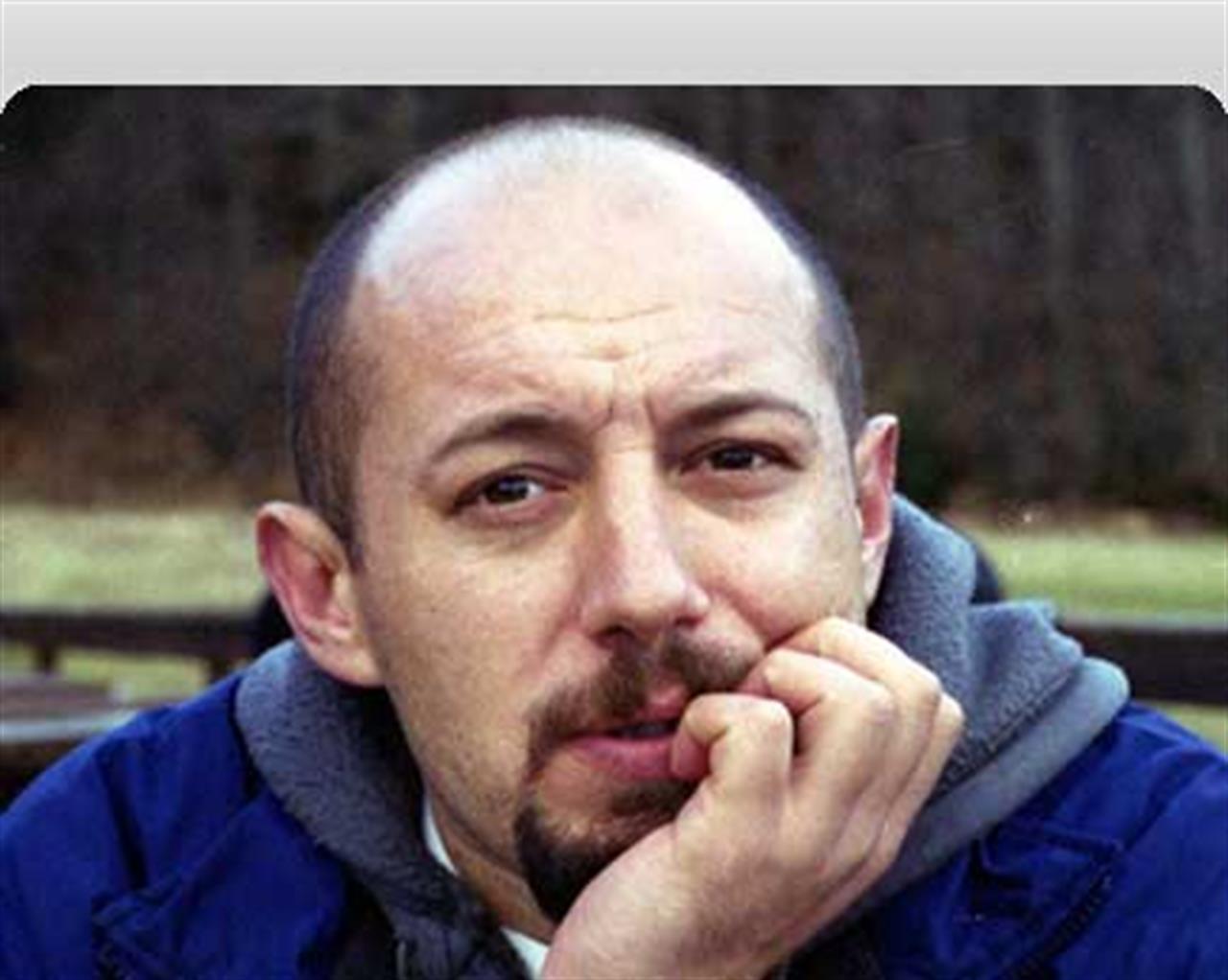

Dejan Georgievski, English editor of One World South East Europe (SEE) talks about the effects of the global financial crisis on the Republic of Macedonia, the young Balkan state which counts just over half a million inhabitants

di Staff

At the beginning of March, EU leaders at an emergency summit in Brussels ruled out a regional bailout plan for eastern Europe.

The area has reportedly been badly affected by the recent financial crisis. What are the risks for eastern European countries specifically, as well as the European community as a whole? And how is the third sector responding?

At the summit, Hungarian Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsany, who was calling for a support fund, declared “we should not allow a new iron curtain to be set up and divide Europe in two parts.”

In the first of our eastern Europe specials, we asked Dejan Georgievski, editor of the English edition of OneWorld SEE, to answer a few questions on the actual effect of the credit crunch in Macedonia, and how the third sector is responding.

How is the credit crunch affecting Macedonia?

At first, there was not much talk about the ongoing crisis in Macedonia. The government initially downplayed the possible effects of the global crisis in the country, which, it commented, was small and not all that well integrated in the global financial systems. Vice-Prime Minister Zoran Stavrevski even projected the 2009 economic growth at three percent, although international financial institutions, like IMF and the World Bank see that as very optimistic, and may be about one percent.

Economic analysts also attacked the proposed 2009 Budget, with projected deficit exceeding 2.8% of the GDP, believing that the Draft-Budget should be reworked and made more realistic and restrictive in terms of public spending.

Naturally, the Government is not likely to be seen as pessimistic, especially in an election campaign for the presidential and local elections, which actually take place today, as I write this. At the start of the campaign, PM Nikola Gruevski came up with a “Macedonian new deal”, announcing plans to invest eight billion EUR in public works over the next seven years, which was quickly dismissed as an unrealistic campaigning trick.

The crunch, naturally, couldn’t and didn’t, in fact, avoid Macedonia, which is a small open economy in which foreign trade greatly exceeds the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP). All industrial sectors have suffered, especially those which are export oriented, with metallurgy industry being hit hardest by last year’s fall of prices of metals on international markets, which effectively meant that they could not cover their production costs. The companies in the sector have tried to ward off the need to lay-off by sending over 2,000 employees on mandatory leave of absence and maintaining production process at the minimum, or working to complete the deals commissioned before the start of the global economic downturn.

The situation is similar in all export oriented sectors, like the textile and food industries. The latter expect the hard hit to come this spring, when traditional importers of Macedonian agricultural produce may leave us because of the recession. The construction sector is in a similar situation, with banks restricting access to loans and falling investments.

As far as the citizens are concerned, we should note, I believe, that they have known little else but economic crisis for the better part of the last quarter of a century, ever since the economic crisis of the early 1980’s in former Yugoslavia. At high unemployment rates (the current national figure is currently about 33-34 percent) their greatest concern is to keep the jobs they have. A poll last week showed that they do intend to try to save as much as possible, mostly on clothes and other consumer goods.

Only yesterday, I learned about a joke circulating by SMS in Serbia – that nothing succeeds in Serbia, so the crisis will fail, too – which could easily apply to Macedonia. Generally speaking, there is an impression that for ordinary citizens, the things may not be much worse than they are now. The biggest concern may be that the global recession may result in loss of jobs for the great number of Macedonia citizens working abroad, which may lead to a drop in the amount of money they send home, assisting the family budgets and, ultimately, the national payments balance. The major problem is the growing unemployment rate. In December 2008 alone, over 1,200 jobs were lost, with a total of more than 3,000 jobs lost in the last quarter of 2008, mostly in metal jobs and the textile industry.

How is civil society responding to it? What could be its impact?

Narrowly speaking, I have not been aware of any actual reaction or response by the civil society. Macedonian civil society organizations have mostly been interested in the March 22 Elections, which are seen as crucial for Macedonian aspirations to join the European Union and NATO. In fact, they have focused on the increasingly authoritarian policies of the Government of centre-right VMRO-DPMNE and what they perceive as actual disinterest of the ruling coalition in integration processes and a tendency to take the country into isolation.

In the wider sense of the word, professional organizations and associations, like farmers’ associations and chambers of commerce have reacted, demanding government assistance for the efforts to overcome the looming crisis.

Does the current financial crisis change the expectations people from Eastern Europe have of Western Europe and their will to move to work and study in member states?

I don’t think this is the case. If anything, I think more people are inclined to think that the only escape from what they see as a hopeless situation in Macedonia is to find a job in Western Europe, or get into a Western university and then stay there and never return. Just to illustrate, tens of thousands of Macedonian, possibly even 60,000 have already applied for and secured Bulgarian citizenship, with an estimated 200,000 more applications already filed. The sole reason for such a move, which requires them to renounce their Macedonian identity, at least declaratively, is the fact that a Bulgarian passport allows free travel to Western Europe, without the need to subject themselves to complicated, expensive and often humiliating visa application procedures.

On the other hand, the people, especially the media, have not failed to notice the consequences that this crisis has on the so-called shared European values, with solidarity being the first to suffer now that the biggest countries like France and Germany have focused their efforts, and by default the efforts of EU institutions where they carry greatest weight, to help themselves first.

Find out more: see.oneworld.net

17 centesimi al giorno sono troppi?

Poco più di un euro a settimana, un caffè al bar o forse meno. 60 euro l’anno per tutti i contenuti di VITA, gli articoli online senza pubblicità, i magazine, le newsletter, i podcast, le infografiche e i libri digitali. Ma soprattutto per aiutarci a raccontare il sociale con sempre maggiore forza e incisività.